Holliday, C.M., Ridgely, R.C., Balanoff, A.M. and L.M. Witmer. 2006. Cephalic vascular anatomy in flamingos (Phoenicopterus ruber) based on novel vascular injection and computed tomographic imaging analyses. Anatomical Record 288A:1031-1041.

The Caribbean flamingo, Phoenicopterus ruber, is one of five species of extant Phoenicopteridae, an avian group probably most closely related to Ciconiiformes (Livezey, 1997; Mayr and Clarke, 2003) although phylogenetic relationships with Anseriformes (Feduccia, 1976, 1978; Olsen and Feduccia 1980) and Podicipedidae (van Tuinen et al., 2001; Mayr, 2004) have also been proposed based on morphological and molecular analyses. Flamingos are easily distinguishable by their rosy or pink feathers (due to the ingestion of carotenoids in their diets), elongate necks and legs, and a conspicuously ventroflexed bill. Flamingos are highly social birds generally found in subtropical and tropical estuarine and briny bodies of water across Latin America, Africa, and India, in addition to numerous front lawns. |

|

Perhaps the most intriguing aspect of flamingo natural history is their feeding behavior, during which they invert their heads and hold their bills nearly horizontal. During these maneuvers, they strain shallow waters for a variety of food items including algae, small invertebrates, and small fish; P. ruber predominately feeds on brine flies and shrimp. Flamingo mouths are peculiarly built to dexterously separate water and unwanted particles from food items using a large, fatty, highly sensitive tongue with numerous fleshy spines complemented by a keeled, lamellate bill. In general, the tongue is used as a rostrocaudally-oriented pump that quickly (5-20 beats/minute) sucks in particulate-laden water and expels unwanted items via a complex set of movements (Jenkin, 1957; Zweers et al., 1995). Food is then ingested using the typical "throw and catch" behavior of most birds. Whereas P. ruber has a rather small maxillary keel, lesser flamingos, James' flamingos, and Andean flamingos have more heavily keeled maxillae (Mascitti and Kravetz, 2002). This keel aids in the mediolateral movement of water and solutes towards the lamellate margins of the tongue and bill. Despite these studies of feeding function, little is known about flamingo head anatomy in general.

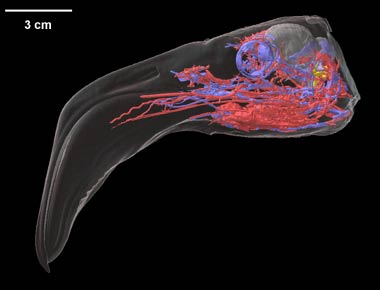

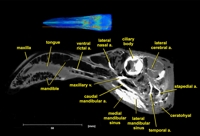

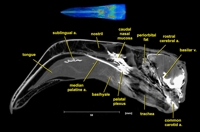

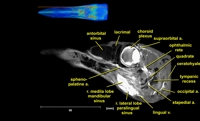

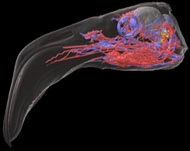

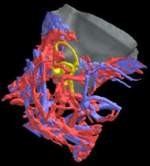

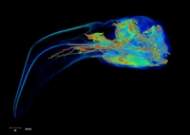

Labeled Volumetric Renderings and Three-dimensional Anaglyphic Stereo Images

Labeled volumetric renderings and anaglyphic (red/cyan) images of flamingo cephalic vasculature. View with standard "3D movie" glasses. For best results view in a dark area.

3D anaglyphic glasses (red/cyan) can be purchased from http://www.berezin.com/3d/3dglasses.htm.

Vascular nomenclature from Sedlmayr (2002). See Sedlmayr (2002) for an analysis of head vasculature in other birds and crocodilians.

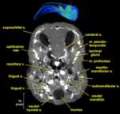

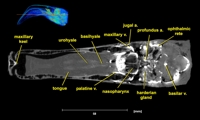

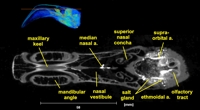

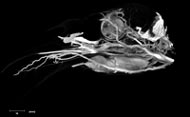

Labeled Slices

Labeled coronal, sagittal, and horizontal slices of flamingo head. Scout image depicts location of slice.

Vascular nomenclature from Sedlmayr (2002). See Sedlmayr (2002) for an analysis of head vasculature in other birds and crocodilians.

Click for a larger image.

See 'Additional Imagery' page for animations.

Literature

Arad, Z., U. Mitgard, and M. H. Bernstein. 1989. Thermoregulation in turkey vultures: vascular anatomy, arteriovenous heat exchange, and behavior. Condor 91:505-514.

* Baumel, J. J. 1993. Systema Cardiovasculare; pp. 407-476 in J. J. Baumel (ed.), Handbook of Avian Anatomy: Nomina Anatomica Avium. Nuttal Ornithological Club, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Baumel, J. J., A. F. Dalley, and T. H. Quinn. 1983. The collar plexus of subcutaneous thermoregulatory veins in the Pigeon, Columba livia: its association with esophageal pulsation and gular flutter. Zoomorphology 102:215-239.

Ericson, P. G. P. 1999. New material of Juncitarsus (Phoenicopteriformes), with a guide for differentiating that genus from the Presbyornithidae (Anseriformes). Smithithsonian Contributions to Zoology 89:245-251.

Feduccia, A. 1976. Osteological evidence for shorebird affinities of the flamingos. Auk 93:587-601.

Feduccia, A. 1978. Presbyornis and the evolution of ducks and flamingos. American Scientist 66:298-304.

Holliday, C. M., R. C. Ridgely, A. M. Balanoff, L. M. Witmer. 2006. Cephalic vascular anatomy in flamingos (Phoenicopterus ruber) based on novel vascular injection and computed tomographic imaging analyses. Anatomical Record 288A:1031-1041.

Homberger, D. G. 1988. Comparative morphology of the avian tongue; pp. 2427-2435 in H. Oeullet (ed.), Acta XIX Congressus Internationalis Ornithologici Vol 2. University of Ottawa Press, Ottawa.

* Jenkin, P. M. 1957. The filter-feeding and food of flamingoes (Phoenicopteri). Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, Biological Sciences 240:401-493.

Livezey, B. C. 1997. A phylogenetic analysis of basal Anseriformes, the fossil Presbyornis, and the interordinal relationships of waterfowl. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, London 121:361-428.

* Mascitti, V., F. O. Kravetz. 2002. Bill morphology of South American flamingos. Condor 104:73-83.

Mayr, G. 2004. Morphological evidence for sister group relationship between flamingos (Aves: Phoenicopteridae) and grebes (Podicipedidae). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, London 140:157-169.

Mayr, G., and J. Clarke. 2003. The deep divergences of neornithine birds: a phylogenetic analysis of morphological characters. Cladistics 19:527-553.

Mitgard, U. 1984. Blood vessels and the occurrence of arteriovenous anastomoses in cephalic heat loss areas of mallards, Anas platyrynchos, Aves. Zoomorphology 104:323-335.

Olsen, S. L., A. Feduccia. 1980. Relationships and evolution of flamingos (Aves: Phoenicopteridae). Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology 316:1-73.

Rich, P. V., and C. A. Walker. 1983. A new genus of Miocene flamingo from East Africa. Ostrich 54:95-104.

Rich, P. V., G. F. van Tets, T. H. V. Rich, and A. R. McEvey. 1987. The Pliocene and Quaternary flamingoes of Australia. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum 25:207-226.

* Sedlmayr, J. C. 2002. Anatomy, evolution, and functional significance of cephalic vasculature in Archosauria. Ph.D. dissertation, Ohio University, 398 pp.

Sedlmayr, J. C., and L. M. Witmer. 2002. Rapid technique for imaging the blood vascular system using stereoangiography. Anatomical Record 267:330-336.

van Tuinen, M. D., B. Butvill, J. A. W. Kirsch, and S. B. Hedges. 2001. Convergence and divergence in the evolution of aquatic birds. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B, Biological Sciences 268:1345-1350.

Vanden Berge, J. C., and G. A. Zweers. 1993. Myologia; pp. 189-247 in Baumel J. J. (ed.), Handbook of Avian Anatomy: Nomina Anatomica Avium. Nuttal Ornithological Club, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Zweers, G. F., H. Berkhoudt, and J. C. Vanden Berge. 1994. Behavioral mechanisms of avian feeding; pp. 241-279 in V. L. Bels, M. Chardon, P. Vandewalle (eds.), Biomechanics of Feeding in Vertebrates. Advances in Comparative and Enviromental Physiology, Vol. 18. Springer-Verlag, Berlin.

* Zweers, G. F., F. de Jong, and H. Berkhoudt. 1995. Filter feeding in flamingos (Phoenicopterus ruber). Condor 97:297-324.

Asterisks (*) denote anatomical literature

Links

Audubon Institute

www.lawnflamingo.com

Phoenicopterus ruber on the Animal Diversity Web (Univ. of Michigan Museum of Zoology).

3D glasses to view stereo images www.berezin.com