Commonly known as thorny devils, the Australian agamid lizard Moloch horridus is protected from predation by numerous sharp spines on its head, body, legs and tail. When threatened, thorny devils tuck their head between their forelegs, leaving the prominent spiny "false head" on the back of their necks in the position of their real head, making them virtually impossible to swallow. They also utilize camouflage to escape detection. Thorny devils are ant specialists, eating virtually nothing else. |

|

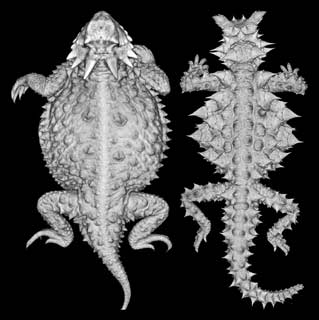

| Phrynosoma cornutum (left) vs. Moloch horridus (right) |

|

North American horned lizards (genus Phrynosoma; see Horned Lizards) are also ant eaters and are distantly related ecological equivalents. No other lizards are as spiny. Moloch and Phrynosoma are often cited as a classic example of convergent evolution. One can argue that camouflage and spines constitute part of an adaptive suite that facilitates specialization on ants, as follows. Because ants are eusocial insects, they constitute a clumped food supply which fosters specialization. However, because ants contain chitin and noxious chemicals such as formic acid, they are not overly nutritious and must be consumed in large quantities. This requires a large stomach. These lizards sit and wait along an ant trail, picking up ants with their tongues. The tank-like body form and spiny protection of thorny devils and horned lizards enables this ecology. |

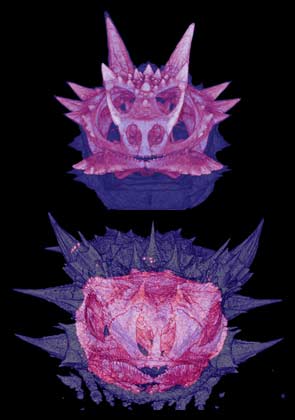

Thorny devils possess more spines than horned lizards, and they are at least as sharp. Using high-resolution X-ray computed tomography we made 3-D digital reconstructions of this thorny devil and of all thirteen living species of horned lizards (see Horned Lizards). Entire preserved specimens were scanned, such that they could be rendered with flesh, then the flesh made transparent and their skeletons rendered. Spines on the heads of horned lizards (right, top) have prominent bony cores on the skull, so we fully expected the thorny devil's skull to show similar bony spines. However, we were surprised that the thorny devil skull has only two small bosses on its parietal and a small ring of calcified blobs around the base of the prominent vertical horns above their eyes (right, bottom). Most of their spines, including the false head, are entirely boneless. Moloch is nevertheless stunningly spiny via dermal armor alone, demonstrating that convergent evolution need not exploit the same mechanisms to achieve a given anatomical endpoint. |  | P. cornutum (top) vs. M. horridus (bottom); semi-transparent flesh in blue, bone in red |

|

About the Species

This specimen was collected October 4, 1992 approximately 138 km east of Laverton, Victoria, Australia. It was made available to The University of Texas High-Resolution X-ray CT Facility for scanning by Dr. Eric Pianka of the Section of Integrative Biology, The University of Texas at Austin. Funding for scanning and image processing was provided by a National Science Foundation Digital Libraries Initiative grant to Dr. Timothy Rowe of The University of Texas at Austin.

Dorsal view of the scanned specimen.

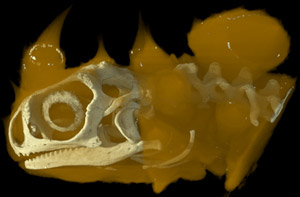

Lateral view of the scanned specimen.

About this Specimen

The head of the specimen was scanned by Richard Ketcham 30 January 2003. It was scanned along the coronal axis for a total of 725 slices, each slice 0.037 mm thick with an interslice spacing of 0.037 mm.

About the

Scan

Literature

Pianka, E. R. 1997. Australia's thorny devil. Reptiles 5:14-23.

Pianka, E. R. and H. D. Pianka. 1970. The ecology of Moloch horridus (Lacertilia: Agamidae) in Western Australia. Copeia 1970:90-103.

Pianka, G. A., E. R. Pianka, and G. G. Thompson. 1998. Natural history of thorny devils Moloch horridus (Lacertilia: Agamidae) in the Great Victoria Desert. Journal of the Royal Society of Western Australia 81:183-190.

Links

Dr. Eric Pianka's thorny devil page

Literature

& Links

Click on the thumbnails below for rotations of the specimen with the flesh rendered semi-transparent.

Front page image.

|  |

Additional Imagery

|