The origin of the domestic dog, Canis familiaris, has been a source of confusion and controversy for many years. Currently, the hypothesis favored by the majority of researchers is the origination of dogs from the gray wolf, Canis lupus, but even that position has been challenged in the past. Yet, for the most part, morphological and molecular data have consistently supported this hypothesis. Dogs and gray wolves share unique allozyme alleles, highly polymorphic satellite alleles, and an extremely similar if not identical mitochondrial DNA (Ruvinsky and Sampson, 2001). Recent genetic studies have even shown that domestication from wolves may have occurred during multiple, independent events and that taming could have begun over 100,000 years ago (Vila and Wayne, 1999). The precise timing of domestication is not easy to resolve since domestic dogs were most likely not distinctive enough to be told apart from wolves until the advent of artificial selection (Ruvinsky and Sampson, 2001). Based on current archeological evidence, the first record of true domestic dogs occurs in the Middle East and dates to around 12000-14000 years ago (Ruvinsky and Sampson, 2001).

Certainly there are remains nearly as old in Europe, North America, and other parts of Asia. The question may no longer be from what species did Canis familiaris arise, but where and how. Morphological comparisons have suggested that domestic dogs most closely resemble the Chinese subspecies Canis lupus chanco (Olsen, 1985). This small wolf does seem a likely candidate, but other studies provide evidence that origination did not come from only one event or lineage. Current research has shown that the different breeds of domestic dog group into four distinct lineages, or clades, and that each group has its own independent connection to Canis lupus (Leonard et al., 2002; Ruvinsky and Sampson, 2001). This assessment seems probable and long before those results were obtained workers had assumed that New World domestic dogs had evolved from North American gray wolves while Old World breeds had developed independently from Eurasian counterparts. Surprisingly, this theory may need to be revised. Not only did Leonard et al. (2002) discover evidence that Canis familiaris is composed of multiple lineages, but also that the majority of New World 'native' breeds actually map onto several 'Old World' clades. Very few breeds turn out to be derived from North American gray wolves. It would appear that more than one Eurasian variety of domestic dog crossed into North America along with humans thousands of years ago. This may not, however, have been the only introduction of European genes, as colonists were reluctant to uphold the pure breeds native to the New World when they began settlement in the 15th century.

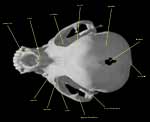

Dorsal View

|

Canis familiaris, dorsal view. |

|

One of the few native breeds that did not mix with European stock is the small Mexican hairless (xoloitzcunitle), a close relative of the Chihuahua. The Chihuahua itself has been crossed with other breeds, most notably brachycephalic forms like the Pekingnese and Pug, giving it a shorter muzzle and relatively flattened face. Other well-known characteristics of the Chihuahua come as the result of the breed’s dwarfism. Most conspicuous is the fontanelle located where the large sagittal crest is found in other canids. In most mammals, as individuals make the transition from juvenile to adult, the bones forming the skull ossify and fuse together. In a Chihuahua’s skull this ossification is usually incomplete, leaving the breed with a gap instead of a suture and a round, broad puppy-like head. A basic dog skull looks quite different, resembling more of an elongate box, but all breeds vary somewhat from this general plan. |

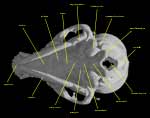

Lateral View

| Canis familiaris, lateral view. |

|

Canis familiaris is actually the most morphologically variable mammal known to science. Interestingly, while domestic dogs exhibit more variation than wild canids, none have developed to resemble the smaller fox-like canids in cranial or limb proportions (see Vulpes vulpes and Urocyon cinereoargenteus) (Ruvinsky and Sampson 2001). As evidenced by Chihuahuas, when domestic dogs shrink in size, their skull shape tends to become more rounded. With true foxes and other small canids, the face and cranium retain an elongate and tapered form. Domestic dogs also tend to have smaller teeth than similarly sized wild species, since a reduction is tooth size is one of the first manifestations of domestication (Ruvinsky and Sampson 2001). In fact, this dental evidence was often used to separate Canis familiaris from small wolves found at archeological sites. Other morphological signs of domestication in the dog include tooth row crowding and a prominent 'stop' (indentation between the eyes where the nasal bones and cranium meet) (Ruvinsky and Sampson 2001). |

Ventral View

|

Canis familiaris, ventral view. |

|

Many of these morphological changes may have come about simply as a side effect of selection for tamer animals. Ruvinsky and Sampson (2001) state that "the diversity in cranial conformation of dogs may stem from the profound changes in size and form that occur during postnatal growth." In other words, compared to other domesticated animals, dogs exhibit the largest disparity between juvenile and adult cranial morphology, and as a result, changes that accelerate or shorten growth during development have more profound effects in dogs. We would expect that bigger dogs, more closely resembling ancestral size, would retain a more elongate and tapered cranium, whereas smaller breeds that can be considered neotenic would tend to have a skull that is rounder, broader, and shortened, just like that of the Chihuahua seen here.

|

About the Species

About this Specimen

This specimen was scanned by Richard Ketcham on 17 April 2006 along the horizontal axis for a total of 556 slices. Each slice is 0.25 mm thick, with an interslice spacing of 0.22 mm (for a slice overlap of 0.03 mm) and a field of reconstruction of 185 mm.

About the

Scan

Literature

Leonard, J. A., R. K. Wayne, J. Wheeler, R. Valadez, S. Guillén, and C. Vilà. 2002. Ancient DNA evidence for Old World origin of New World dogs. Science 298:1613-1616.

Miller, M. E. 1993. Miller's Anatomy of the Dog, 3rd edition. Howard E. Evans, (ed.), W.B. Saunders Company, Philadelphia, 1113 pp.

Olsen, S. J. 1985. Origins of the Domestic Dog. The University of Arizona Press, Tucson, Arizona, 118 pp.

Ruvinsky, A., and J. Sampson. 2001. The Genetics of the Dog. CABI Publishing, New York, New York, 564 pp.

Vilà, C., and R.K. Wayne. 1999. Hybridization between wolves and dogs. Conservation Biology 13:195-198.

Literature

& Links

Front page image.

|  |

Additional

Imagery

|